We hear it so often in the office when someone brings in an older cat or dog: “She was doing fine until the end of last week, but then over the weekend she just stopped eating and drinking, and I don’t think she’s moved from her bed in the corner for at least 24 hours now. What happened? What symptoms did I miss?” Even the best pet parents can end up feeling guilty because they think maybe they weren’t paying enough attention until their animal is seriously ill.

But the truth is that cats and dogs are remarkably good at hiding pain and even serious illness. Most experts think this is a holdover from their days as wild animals, where exhibiting weakness would make them a target for predators, and it’s probably also that, unlike humans, pets don’t reflect on (or worry about) what a new pain or symptom means – they just get on with life.

All of this can make it tough for pet parents to know when an illness needs aggressive treatment, requires palliative care, or is so serious that euthanasia should be considered. This is particularly tough when it comes to cats: We’ve all met or lived with house cats who have lived to very ripe old ages of 17, 19 – even 21. (Of course outdoor cats hardly ever reach these advanced ages, but an indoor cat isn’t considered ‘geriatric’ until about 15.)

Knowing when to treat, wait – or make a big decision.

Older cats tend to suffer from a number of serious illnesses, from renal failure and heart disease to diabetes and cancer. Some of these, like diabetes, can be controlled with strict regimens of medication; others, like hemangiosarcoma, require surgery and the prognosis can be uncertain.

How do you determine which course of action is the best for your cat? It can be hard to think clearly when a beloved pet is ill.

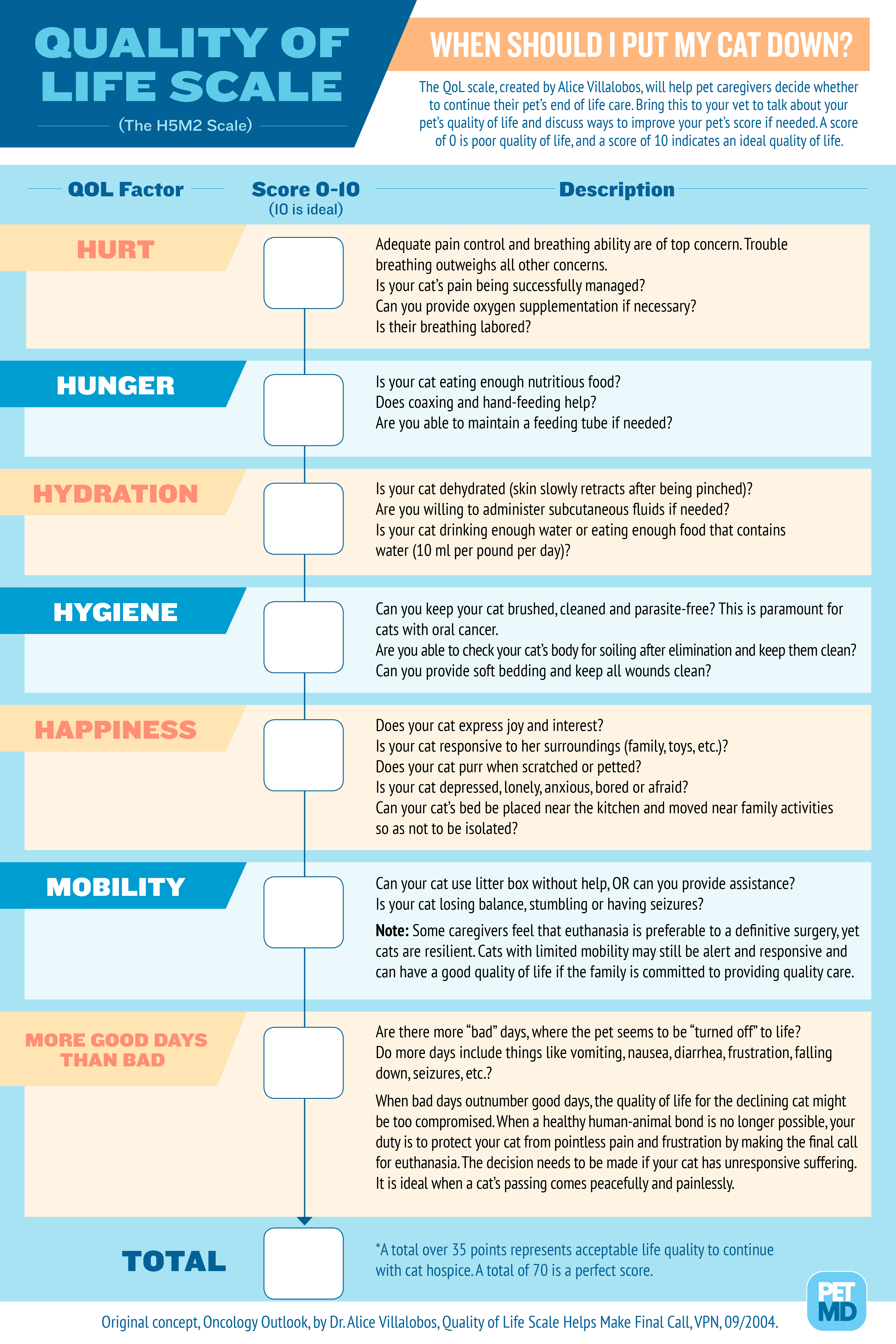

We’ve found that it can be helpful to use this Quality of Life Scale (also known as the H5M2 Scale). It helps you think through the different dimensions of your cat’s day-to-day life, and help you come to a more objective assessment of their true quality of life. And it makes it easier to observe and document your cat’s activity over a few days, which is crucial to really understanding what’s happening with your cat.

(Full disclosure: People tend to think that veterinarians and vet techs/assistants are able to be more detached and objective about their pets than other people, but in fact when our pets are sick, we’re just as emotional as anyone else. So yes, we do use this scale when we find ourselves faced with a big decision.)

Infographic by petMD.com

Worried about your older cat?

Give us a call or stop by the office – we’d be happy to talk to you about the best ways to ensure that your older cat stays healthier, longer.